Untitled ("Hi Folks"), 1965

Joe Brainard (1941–1994) was an American artist and writer associated with the New York School. His prodigious and innovative body of work included assemblages, collages, drawing, and painting, as well as designs for book and album covers, theatrical sets and costumes. In particular, Brainard broke new ground in using comics as a poetic medium in his collaborations with other New York School poets.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joe_Brainard

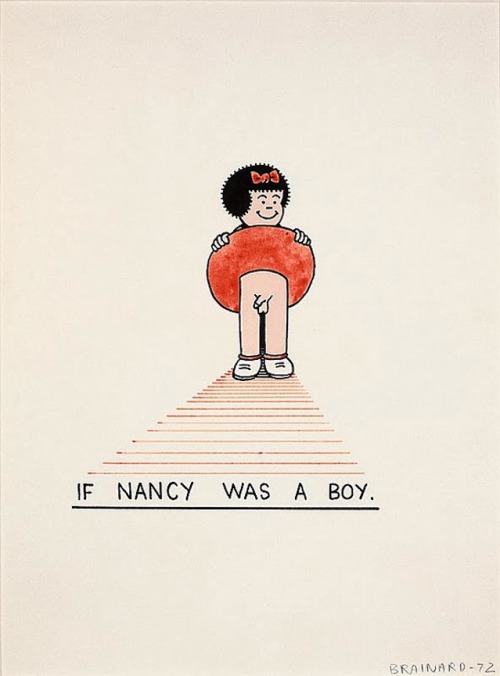

If Nancy Was an Acid Freak, 1972

From 1963 to 1978 Joe Brainard created more than one hundred works of art that appropriated the classic comic strip character Nancy and sent her into an astonishing variety of spaces, all electrified and complicated by the incongruity of her presence.

These works exude a beguiling balance of mischief and innocence, irreverence and wonder, spontaneity and calculation. Together they accumulate into a sophisticated and complex work of great wit and joy, rich with metaphor, and equal parts surprise and subtlety.

http://www.sigliopress.com/books/nancy.htm

Nancy diptych, 1974

Nancy is hardly the universal image of beauty. The title character of Ernie Bushmiller’s comic strip is ungainly, sporting a potato head, hyphen nose, and crenellated hair with protruding mothlike bow. She is always crisply drawn, however, and her smile is strangely reassuring, even as it suggests, Mona Lisa–like, that she might have something to keep quiet about.

In 1963, the year a graphic artist named Harvey Ball first put two dots and a curve inside a circle to create the Smiley Face, another artist began making use of Nancy’s very similar ready-made grin.

Poet and artist Joe Brainard (1942–1994) was living in New York on next to no money, sharing apartments with poet-friends from his hometown (more about them shortly). To conserve art supplies, he made collages, some of them featuring comic strip characters. In one, Nancy shares the frame with colleagues from other strips, running off the top of what appears to be a Japanese real estate ad, while Li’l Abner and Daisy Mae take up space at the bottom of the image.

Before long, Brainard came to recognize what many cartoonists knew then and continue to acknowledge: Nancy is always likable, even when her trademark smile is replaced by a worry-frown and three flying beads of sweat. Blank to the point of being a bit of a Rorschach blot, she never stops seeming friendly, vulnerable, resilient, average, or unassuming.

At the start of their seminal 1988 semiotics study “How to Read Nancy,” cartoonists Paul Karasick and Mark Newgarden anticipated the hypothetical reply to their title, “You might as well explain how to read a stop sign.” Zippy cartoonist Bill Griffith described this foregone-conclusion quality like so: “You don’t ‘enter’ a Nancy strip, it’s slapped up on a billboard inside your head by a guy wearing pressed overalls and a neatly trimmed moustache.” Understanding Comics author Scott McCloud took the point to the extreme: “Ernie Bushmiller’s comic strip ‘Nancy’ is a landmark achievement: A Comic so simply drawn it can be reduced to the size of a postage stamp and still be legible; an approach so formulaic as to become the very definition of the ‘gag-strip’; a sense of humor so obscure, so mute, so without malice as to allow faithful readers to march through whole decades of art and story without ever once cracking a smile.”

Jordan Davis

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/article/182198

Untitled (Nancy Descending a Staircase), c. 1969

Among cartoon characters, Brainard reserved special affection for Nancy, the resolutely plucky woman-child whose backyard philosophy had been chronicled in the dailies since 1933, and whom the artist adopted as his alter ego. Nowhere is this more evident than in If Nancy Was a Boy (1972), which depicts the scamp lifting her skirts to reveal a benignly cartoonish penis. Nancy offered Brainard a way of mischievously addressing his own homosexuality, his drawing one of a series of hilarious small-scale works featuring the satirical permutations of his graphic surrogate. The art-historical in-jokes of Nancy as a Da Vinci Sketch (1972) or Nancy as a De Kooning (1975) contrast with darkly comic images such as If Nancy was Bright’s Disease (1972), which transformed the little tike into a kidney lesion, her image grafted onto an illustration from a medical dictionary.

Having a muse with such a mutable ‘can-do’ attitude gave Brainard licence to play at style while waggishly disregarding the traditional importance of a consistent artistic signature. He noted his work’s apparent lack of visible authorship, and it is not surprising that he eventually permitted himself to disengage from the public role of artist. In his memoirs Brainard wrote that art was simply ‘a way of keeping busy. A way of showing my appreciation of things I especially like. A way of pleasing people. (Which pleases me.)’

James Trainor

http://www.frieze.com/issue/review/joe_brainard/

If Nancy Had an Afro, 1972

Brainard spin- cycled high and low to produce chuckle inducers like “Picasso Nancy” and “If Nancy Was André Breton at Eighteen Months.” Low and even lower are lubriciously evident in the numerous visual sex jokes, in which, for instance, smiling Nancy’s globular head is set on the splayed and naked body of a porn actress; or she’s made to wave gaily from a young man’s crotch in “If Nancy Was a Sailor’s Basket.” The campy innuendo is enriched by the inclusion of non sequiturs and otherwise-absurdist bons mots from Brainard’s poet pals. One image (Bill Berkson contributed the text) shows our gal and the imported cartoon character Henry in flagrante delicto as the off-the-wall line “In England ‘wet’ means ‘stupid’” graces the couple’s copulatory bliss (of course, the mouthless Henry’s delight must be inferred). Another image presents Nancy completely dark, as if she were a photo negative; her thought bubble has been filled in by Frank Lima: “I have burned down the sky,” she opines. Brainard was a master of life’s microcomedies, the unheard laughter that courses through any truly alert consciousness. And Nancy, with that bow like a pulsating noodle in her frizzy hair, is as good a Descartes as any for our age.

Albert Mobilio

http://www.bookforum.com/inprint/015_01/2288

If Nancy Was A Boy, 1972

No comments:

Post a Comment